Laboratory vs Synchrotron SAXS: when to choose one or the other ?

When you hear Small Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS) do you automatically think of a large synchrotron ring and tens of meters long instruments?

While these powerful machines offer the possibility to perform impressive experiments, laboratory SAXS instruments have seen great advances in recent years, making them increasingly versatile. Technical improvements in laboratory X-ray sources and detection systems have also considerably decreased the measurement times.

The question arises thus, when should one be preferred over the other, but also how can the two complement each other?

Data quality in the lab is today comparable to synchrotron’s

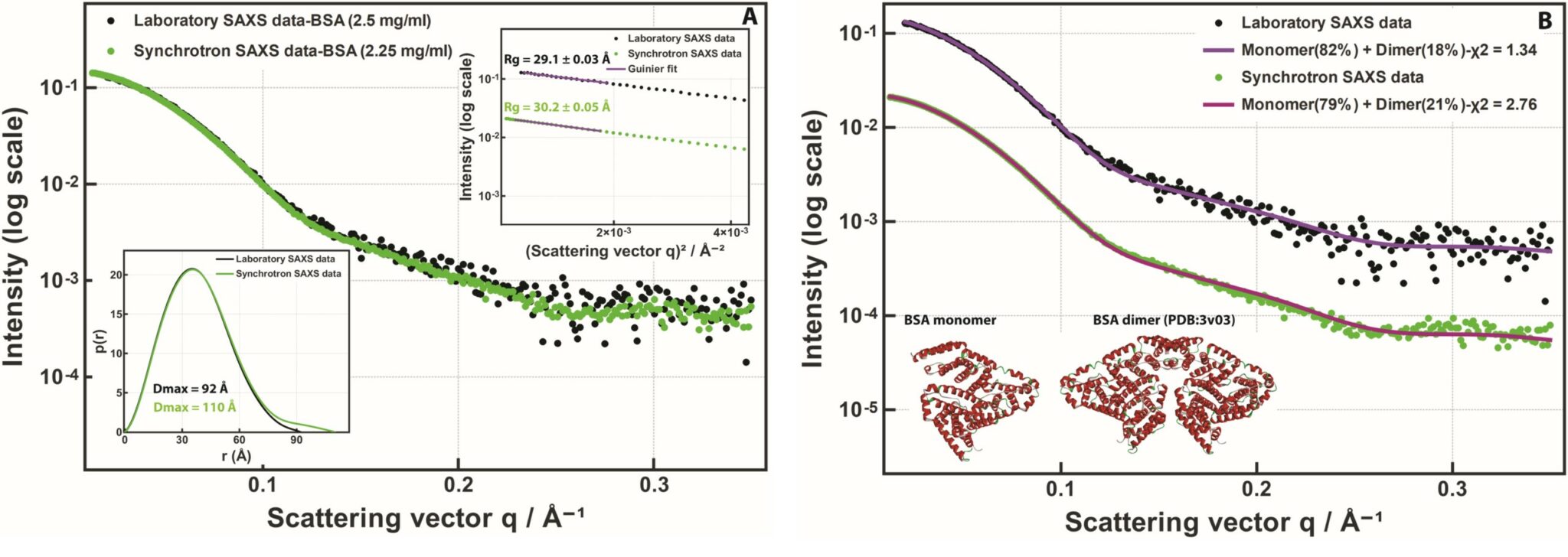

Laboratory instruments can provide high-quality data with accurate data analysis. For example, one of the most extensively investigated biological systems is proteins in solution, which can be analyzed through SAXS measurements. SAXS enables the characterization of closely related molecules, including the monomer-dimer equilibrium in solution, which is not easily achievable using other biophysical techniques.

In Figure 1 (A), SAXS data collected on a Xenocs BioXolver instrument are directly compared with synchrotron SAXS data collected from the same bovine serum albumin protein on the P12 beamline at the PETRA III storage ring (DESY, Hamburg, Germany) [1] (the synchrotron data has been sourced from the SASBDB entry SASDDN3 [2]). The great agreement between the two data sets is evident, even if the signal-to-noise ratio is not the same for the two.

Bovine serum albumin (BSA) in solution is mostly monomeric but it is known that a small number of dimers is typically present. To characterize the oligomeric composition, the SAXS data can be fitted with a weighted sum of scattering patterns computed from the atomic models of the monomer and the dimer (see Figure 1 (B)). Both data sets revealed the presence of a small dimer fraction with similar monomer to dimer volume ratios: 82:18% for the laboratory data and 79:21% for the synchrotron data.

Given the high accuracy of laboratory instruments, it is possible to obtain a sensitive detection of the dimer or large oligomer ratio in solution that matches well the synchrotron results.

Figure 1. (A) SAXS data collected on bovine serum albumin (BSA) solutions. Black dots: SAXS data from 2.5 mg/ml BSA in 50 mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.3 measured for 10 minutes on Xenocs BioXolver with a MetalJet source. Green dots: SAXS data from 2.25 mg/ml BSA in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5 measured for 5 seconds at the synchrotron beamline P12 (EMBL/DESY), taken from SASBDB [2] entry SASDDN3. The Guinier plot and the pair distance distribution functions are sh own in the insets. (B) The same data fitted with a monomer:dimer mixture. Solid lines: SAXS patterns computed from mixtures of the BSA monomer and dimer models taken from PDB: 3v03 (shown in the inset) [3].

There are however some instances in which synchrotron beamlines are the go-to technique:

- For studying very fast processes the high flux of a synchrotron enables sub-millisecond time resolution. Laboratory sources offer the possibility to perform dynamical studies with a timescale in the range of seconds. At the opposite end, if you are interested in very slow processes, laboratory sources should be privileged for such long-duration in-situ monitoring experiments as beamtime is more readily available and long time slots can be granted.

- For studies that require microbeam scanning SAXS or Wide Angle X-ray Scattering (WAXS). Instruments at a synchrotron can offer collimated beams down to 100 x 100 nm² with a flux as high as 1011 ph/s [4] enabling nanobeam scanning in reasonable timeframes. The trade-off between flux and beam size, which needs to be considered more carefully in the case of less brilliant laboratory sources, limits the latter to a few tens of microns.

Laboratory SAXS offers the advantage of easy accessibility

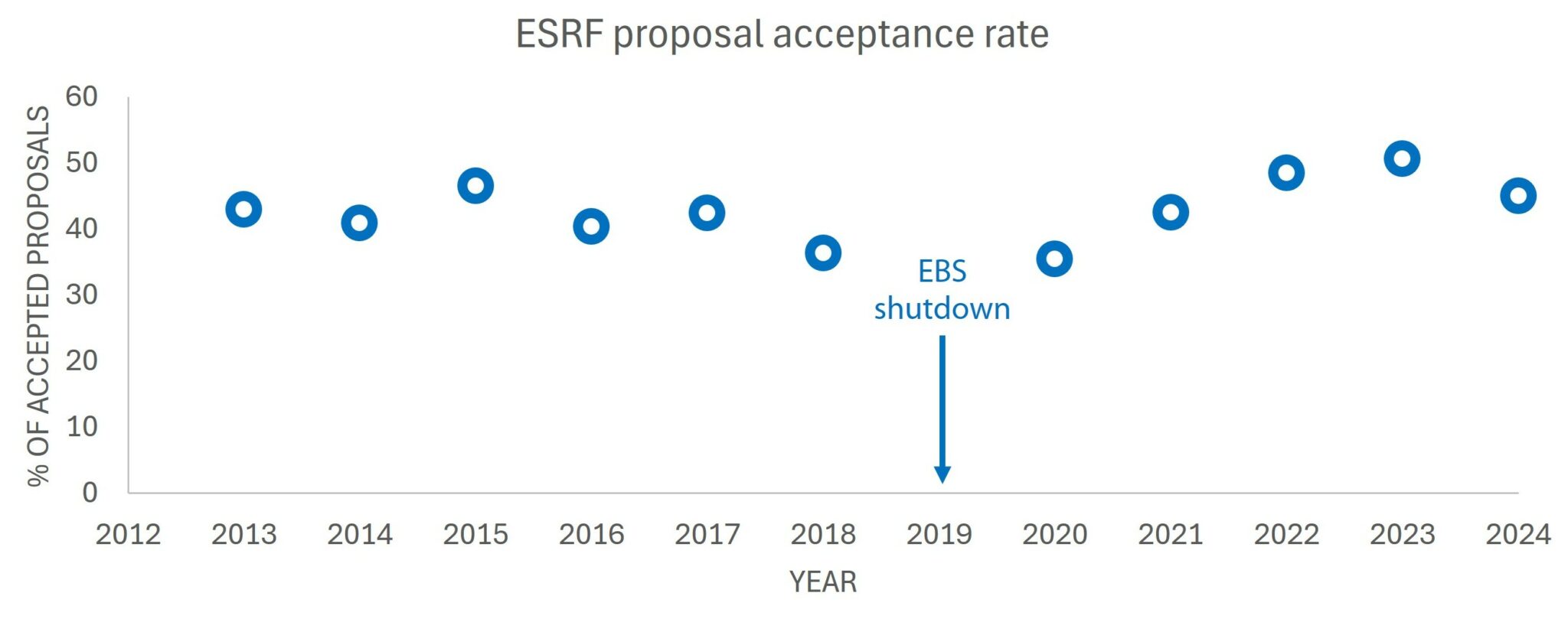

Beamtime access to laboratory instruments is more readily available compared to synchrotron sources. Proposal acceptance rates at a synchrotron are usually below 50% (see Figure 2) and can go as low as 30% depending on the instrument requested. To be granted beamtime at a synchrotron, you will need to prove, through the submitted proposal, that your research would greatly benefit from the increased flux compared to a laboratory source. Furthermore, the proposal should demonstrate that detailed knowledge about the sample is already available. In this regard, laboratory SAXS is an excellent tool to pre-characterize samples.

Figure 2. Acceptance rates at the European Synchrotron. Data extracted from [5].

Use the complementary of laboratory and synchrotron SAXS to enhance your research!

There are many instances in which the two measurements, in the lab and at the synchrotron, are complementing each other in order to either prepare for more efficient use of synchrotron facilities or to obtain a complete picture of a study. An in-house system provides the opportunity to:

- perform proof-of-principle measurements and preliminary analysis which can be very valuable when preparing a synchrotron proposal. In this regard, having full control of the experimental set-up is a major advantage of a home-lab instrument over a synchrotron-based one.

- improve the sample preparation process by offering the possibility to test a large number of samples and respond in real-time to the results. This operation is key in finding the right experimental conditions and it is an important prerequisite of any beamtime at a synchrotron.

- select the best samples to be used in a synchrotron experiment. Routine characterization of various sample morphologies and evolution as a function of certain parameters (such as temperature) ensures that the right samples can be shipped in optimal conditions to synchrotrons.

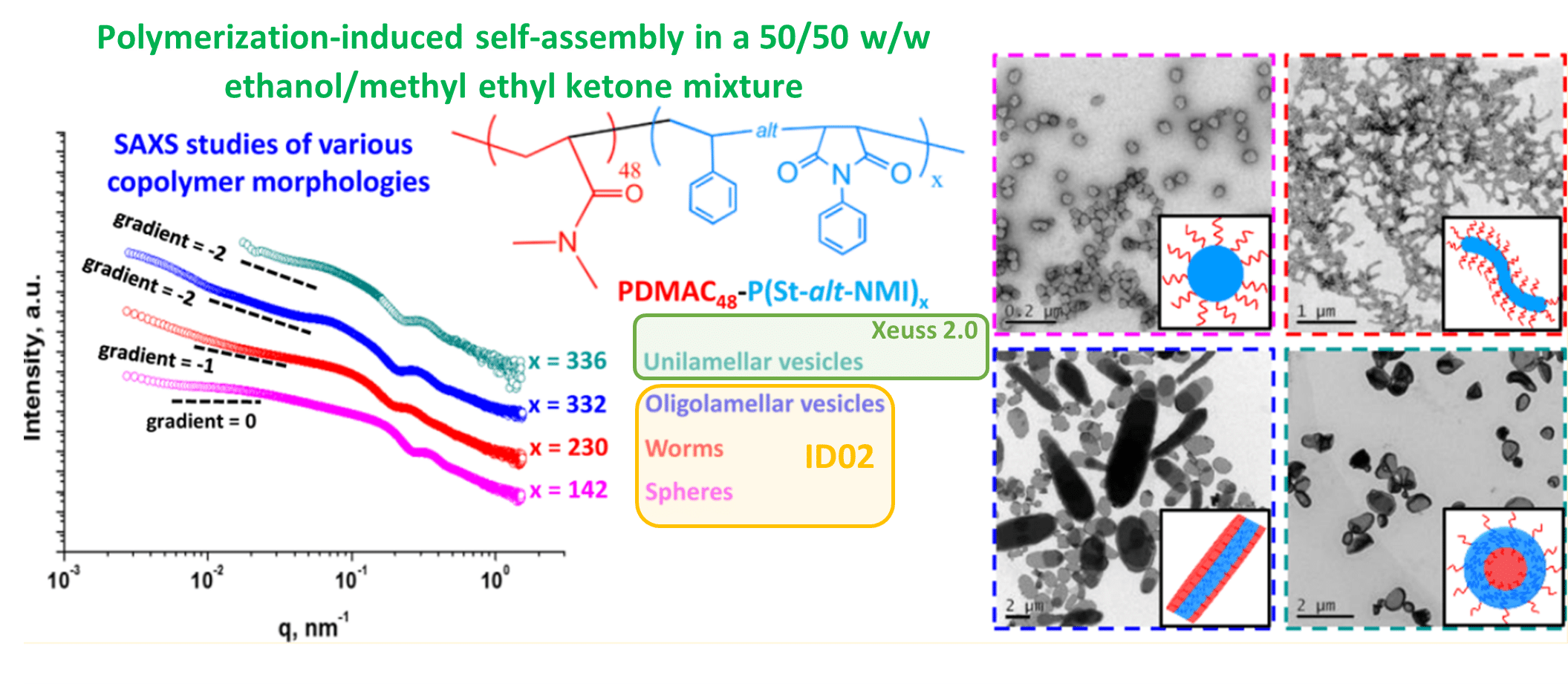

- complete study with additional data in the case of insufficient synchrotron beamtime. There are various reasons for which additional data might be required in order to attain a complete understanding of a particular topic, limited synchrotron experimental time or inability to respond in real-time to the results and prepare additional samples being only two of them. Additional data could also be requested for publication during the review process. This imposes additional time constraints as answers need to be provided within the resubmission time. As mentioned before, the data quality of state-of-the-art laboratory instruments and synchrotron-based ones . This makes it possible to use a combination of laboratory and synchrotron data (as displayed in Figure 3) to obtain a complete picture of the research.

Figure 3. 1D SAXS plots obtained for four pure PDMAC48−P(St-alt-NMI)x copolymer morphologies recorded on a Xeuss 2.0 laboratory instrument and on the ID02 synchrotron beamline at the ESRF. Associated TEM images can be observed in the right-hand side if the figure [6]. Credit: Macromolecules 2016, DOI: 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b01563.

In a nutshell…

Recent advances in X-ray sources, beam collimation and detection have brought high-quality X-ray scattering measurements closer to scientists through in-house laboratory SAXS/WAXS instruments.

In essence, for most applications, the nanostructure of various samples can be probed, over a broad length scale, using laboratory SAXS instruments including SAXS/WAXS/GISAXS/GIWAXS/X-ray reflectometry experiments.

While large-scale facilities will continue to be instrumental for challenging samples, if you would like to promptly understand the nanostructure of your samples, a laboratory X-ray scattering instrument is the solution. Even though measuring time will be longer than that of a synchrotron source, the time lag in answering your question will surely be shorter since you will be bypassing delays generated by proposal submission and acceptance, beamtime scheduling and traveling times. For many types of samples, synchrotron SAXS is not even necessary as the structure can be easily and fully studied with a laboratory source. Moreover, if you have been granted synchrotron beamtime, laboratory measurements can prove essential in optimizing experimental parameters to ensure an optimal outcome or to complete your dataset when back home.

[1] C. E. Blanchet, A. Spilotros, F. Schwemmer, M. A. Graewert, A. Kikhney, et al., Versatile Sample Environments and Automation for Biological Solution X-Ray Scattering Experiments at the P12 Beamline (PETRA III, DESY), J Appl Cryst 48, 2 (2015). DOI: 10.1107/S160057671500254X.

[2] A. G. Kikhney, C. R. Borges, D. S. Molodenskiy, C. M. Jeffries, and D. I. Svergun, SASBDB: Towards an Automatically Curated and Validated Repository for Biological Scattering Data, Protein Science 29, 66 (2020). DOI: 10.1002/pro.3731.

[3] K. A. Majorek, P. J. Porebski, M. Chruzcz, S. C., Almo, and W. Minor, Crystal structure of bovine serum albumin. (2012). Available at: https://www.rcsb.org/structure/3v03

[4] ESRF synchrotron, ID13 – MICROFOCUS BEAMLINE. Retrieved March 15, 2022, from https://www.esrf.fr/UsersAndScience/Experiments/XNP/ID13

[5] ESRF report: ESRF Highlights 2020-2024 [Online]. Available at: https://www.esrf.fr/UsersAndScience/Publications/Highlights

[6] P. Yang, O. O. Mykhaylyk, E. R. Jones, and S. P. Armes, RAFT Dispersion Alternating Copolymerization of Styrene with N-Phenylmaleimide: Morphology Control and Application as an Aqueous Foam Stabilizer, Macromolecules 49, 6731 (2016). DOI: 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b01563.