How do PEGylated lipid nanoparticles organize to enable mRNA delivery?

Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) are the leading delivery vehicles for mRNA therapeutics. Their performance is closely tied to internal structure and phase organization, which affect stability, encapsulation, and efficient mRNA release. While standard techniques such as dynamic light scattering (DLS) and zeta potential measurements provide information on particle size and surface charge, they do not reveal how lipids and mRNA are organized inside the nanoparticle. High-resolution methods like cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) can provide such detail, but they are often low-throughput and less suited for rapid screening of multiple formulation conditions.

Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) bridges this gap by delivering detailed insights into the structure, lamellarity, and internal organization of LNPs [1-6]. Similar structural parameters are considered critical quality attributes in FDA guidance for liposomal drug formulations [7]. SAXS also enables direct insight into mRNA encapsulation [4,6,8,9], lipid bilayer structure, [10] phase identification [1,2,8,11-12] and structural stability under varying conditions such as pH, [2,11,12] temperature, [2] and lipid composition [1,2,5,10]. When combined with wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS), crystalline phases within LNP formulations can also be identified, [13] supporting formulation optimization and quality control assessment.

Recently, researchers from the mRNA Center of Excellence at Sanofi demonstrated this potential by using laboratory SAXS/WAXS to characterize PEGylated mRNA–LNPs, highlighting how structural fingerprints correlate with delivery efficiency [1].

To investigate how PEGylation influences the internal organization of mRNA–lipid nanoparticles, three formulations were compared. Two served as reference systems: one containing DMG–PEG2000 (Std1) and another with DMG–PEG5000 (Std2). The former is widely used in LNP development, whereas the latter was identified after screening dozens of PEGylated lipids. The third was an optimized formulation (OPT), which also used DMG–PEG5000 but underwent further refinement through a design-of-experiments (DoE) approach. This strategy enabled systematic exploration of lipid composition to identify structural features most favourable for efficient mRNA delivery. By analyzing these three representative systems, researchers could directly assess how PEG chain length and compositional optimization affect the balance between lamellar and hexagonal domains, structural order, and ultimately, delivery-relevant properties [1].

Structural fingerprints of mRNA–LNPs: Lamellar and hexagonal domains revealed by SAXS

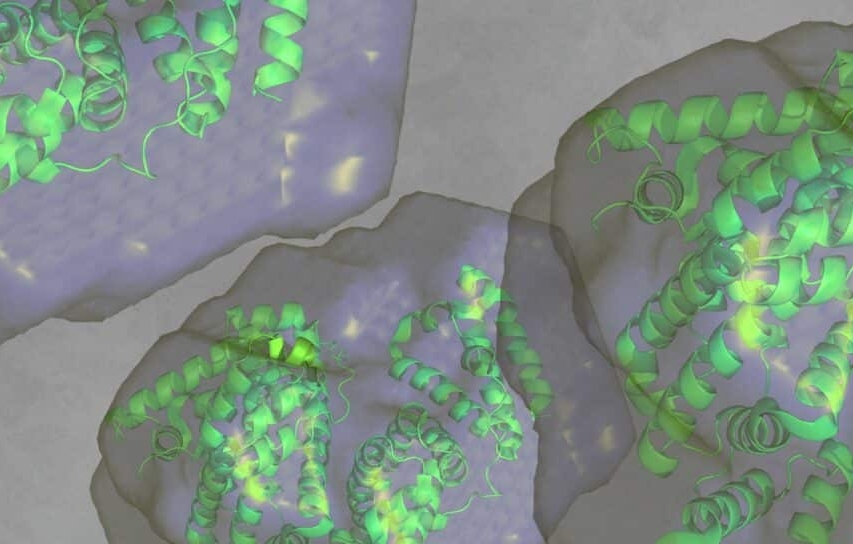

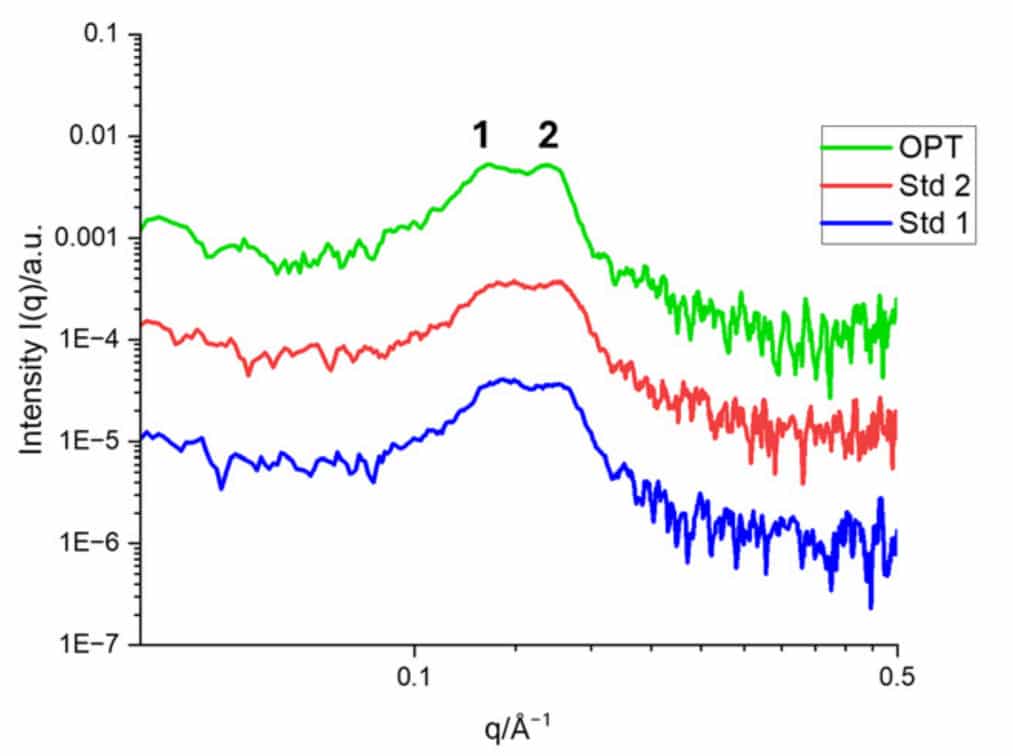

SAXS profiles of the three formulations revealed two distinct structural fingerprints: a Bragg peak at q ≈ 0.13 Å⁻¹ corresponding to an inverted hexagonal phase, and another at q ≈ 0.16 Å⁻¹ corresponding to a multilamellar phase (Fig. 1). Cryo-EM confirmed the coexistence of both phases, underlining the reliability of SAXS for in-solution phase identification. For the optimized (OPT) formulation, the repeat distances were ~ 4.0 nm for the lamellar phase and ~ 4.9 nm for the hexagonal phase, in agreement with cryo-TEM values.

Figure 1. SAXS profiles of the OPT mRNA-LNP formulation and two standard reference formulations Std1 and Std2 formulations in 10% Trehalose. Credit: Nanoscale, 2025 DOI: 10.1039/D5NR00433K

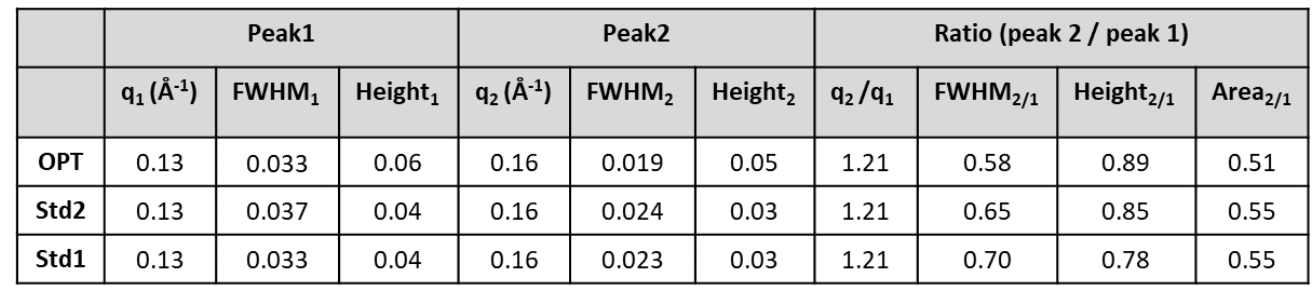

Table 1. SAXS peak features of the OPT, Std 2, and Std 1 formulations in 10% Trehalose.Credit: Nanoscale, 2025 DOI: 10.1039/D5NR00433K

SAXS uncovers pH-driven structural transitions linked to mRNA release

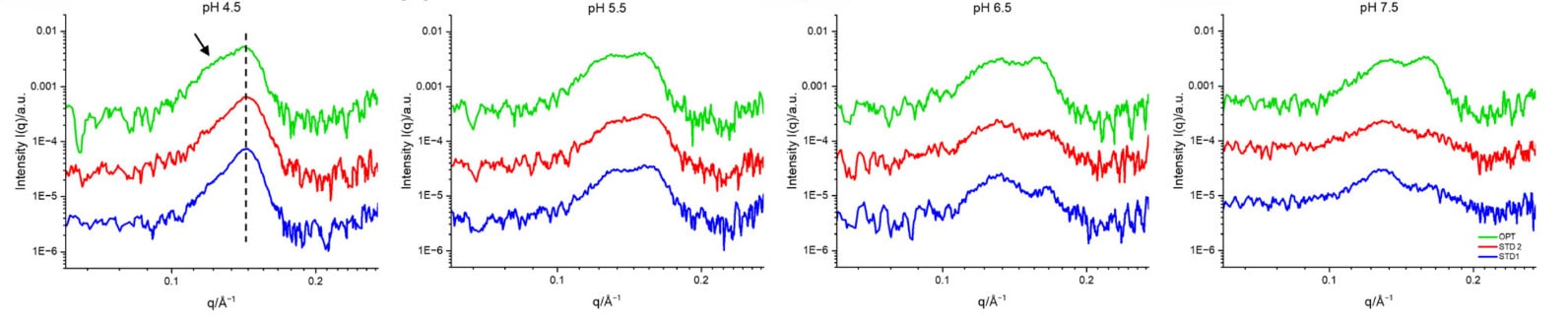

To study the influence of pH, an essential parameter that mimics the endosomal environment, SAXS measurements were used to monitor pH-dependent structural transitions across the three formulations.

At near-physiological pH (7.5), the optimized (OPT) formulation displayed strong signatures of both lamellar and hexagonal phases, while the reference formulations (Std1, Std2) showed weaker multilamellar features (Fig. 2).

As the pH decreased, Std1 and Std2 underwent a structural reorganization, developing sharper lamellar and hexagonal peaks that reflected a transition from less ordered to more well-defined structures. In contrast, the OPT formulation consistently maintained the strongest inverted hexagonal peak, even at pH 4.5 (Figs. 2–3). This observation is consistent with a pre-organized fusogenic structure that supports endosomal escape and efficient mRNA release.

Figure 2. SAXS profiles of the OPT, Std 2, and Std 1 formulations mixed with citrate-phosphate buffers at different pH values. Credit: Nanoscale, 2025 DOI: 10.1039/D5NR00433K

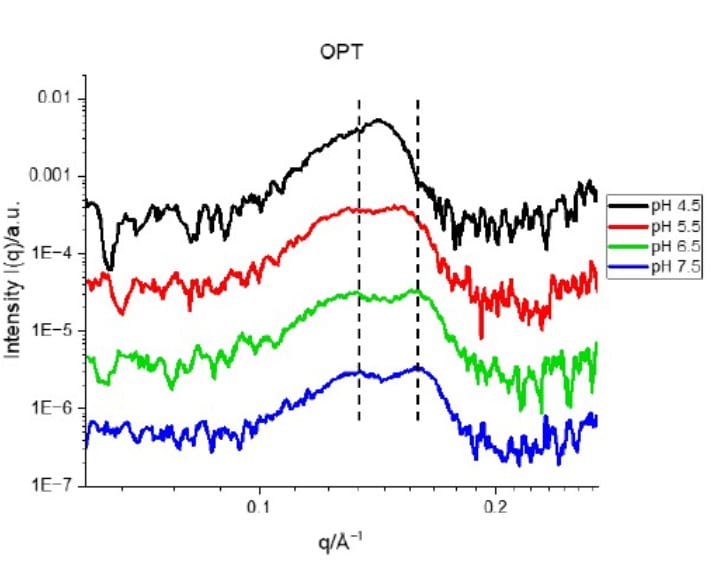

Figure 3. SAXS profiles of the OPT mRNA-LNP formulation mixed with citrate- phosphate buffers at different pH values. Credit: Nanoscale, 2025 DOI: 10.1039/D5NR00433K

Additionally, SAXS detected a shift of Bragg peaks positions toward lower q-values at acidic pH, corresponding to an increase in d-spacing (Fig. 3). This expansion suggests water uptake by the nanoparticles, a structural adjustment that further reflects their responsiveness to the endosomal environment.

From nanostructure to delivery: Key takeaways from SAXS/WAXS

These results demonstrate the ability of laboratory SAXS/WAXS to resolve the internal organization of LNPs, providing quantitative insight into repeat distances of lipid layers (lattice spacing) and the degree of structural regularity (nanodomain order). These findings were fully consistent with cryo-EM results, while offering the advantage of high-throughput, in-solution characterization.

Importantly, SAXS/WAXS detected well-defined structural fingerprints and tracked their pH-dependent transitions, a feature critical for understanding endosomal escape. The optimized formulation exhibited sharper, more ordered hexagonal domains and a structural bias toward the fusogenic phase, consistent with enhanced mRNA release.

By directly linking nanostructure to delivery-relevant properties, SAXS/WAXS supports rapid screening of formulations across multiple conditions, structure–activity relationship studies, and robust quality assessment in industrial workflows. Together, these results establish SAXS/WAXS as a reliable, high-throughput tool for the design, optimization, and quality control of next-generation mRNA–LNP therapeutics.

The research was originally published in the following article: [1] L. Liu, J-H. Kim, Z. Li, M. Sun, T. Northen, J. Tang, E. Mcintosh, S. Karve, F. DeRosa. PEGylated lipid screening, composition optimization, and structure-activity relationship determination for lipid nanoparticle-mediated mRNA delivery. Nanoscale. 17. (2025) DOI: 10.1039/d5nr00433k.

References

[1] L. Liu, J-H. Kim, Z. Li, M. Sun, T. Northen, J. Tang, E. Mcintosh, S. Karve, F. DeRosa. PEGylated lipid screening, composition optimization, and structure-activity relationship determination for lipid nanoparticle-mediated mRNA delivery. Nanoscale. 17, 11329–11344. (2025) DOI: 10.1039/d5nr00433k.

[2] R. Pattipeiluhu, Y. Zeng, M.-M.-R.-M. Hendrix, I.-K. Voets, A. Kros, T.-H. Sharp. Liquid crystalline inverted lipid phases encapsulating siRNA enhance lipid nanoparticle mediated transfection. Nat. Commun. 15, 1303. (2024) DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-45666-5.

[3] H.-M. Dao, K. AboulFotouh, A.-F. Hussain, A.-E. Marras, K.-P. Johnston, Z. Cui, R.-O. Williams 3rd. Characterization of mRNA lipid nanoparticles by tlectron density mapping reconstruction: X-ray scattering with density from solution scattering (DENSS) algorithm. Pharm. Res. 41, 501-512. (2024) DOI: 10.1007/s11095-024-03671-9.

[4] J. Gilbert, F. Sebastiani, M.-Y. Arteta, A. Terry, A. Fornell, R. Russell, N. Mahmoudi, T. Nylander. Evolution of the structure of lipid nanoparticles for nucleic acid delivery: From in situ studies of formulation to colloidal stability. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 660, 66-76. (2024) DOI: 10.1016/j.jcis.2023.12.165.

[5] C. Wilhelmy, I.-S. Keil, L. Uebbing, M.-A. Schroer, D. Franke, T. Nawroth, M. Barz, U. Sahin, H. Haas, M. Diken, P. Langguth. Polysarcosine-Functionalized mRNA Lipid Nanoparticles Tailored for Immunotherapy. Pharmaceutics. 15, 2068. (2023) DOI: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15082068.

[6] US Food and Drug Administration. Liposome Drug Products: Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls; Human Pharmacokinetics and Bioavailability; and Labeling Documentation. In Guidance for Industry.(CDER); Food and Drug Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, (2018).

[7] L. Cui, M.-R. Hunter, S. Sonzini, S. Pereira, S.-M. Romanelli, K. Liu, W. Li, L. Liang, B. Yang, N. Mahmoudi, A.-S. Desai. Mechanistic studies of an automated lipid nanoparticle reveal critical pharmaceutical properties associated with enhanced mRNA functional delivery in vitro and in vivo. Small, 18, e2105832. (2022) DOI: 10.1002/smll.202105832.

[8] S. Patel, N. Ashwanikumar, E. Robinson, Y. Xia, C. Mihai, J.-P. Griffith 3rd, S. Hou, A.-A. Esposito, T. Ketova, K. Welsher, J.-L. Joyal, Ö. Almarsson, G. Sahay. Naturally-occurring cholesterol analogues in lipid nanoparticles induce polymorphic shape and enhance intracellular delivery of mRNA. Nat Commun. 11, 983. (2020) DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-14527-2.

[9] J.-A. Kulkarni, M.-M. Darjuan, J.-E. Mercer, S. Chen, R. Van Der Meel, J.-L. Thewalt, Y.-Y.-C. Tam, P.-R. Cullis. On the Formation and morphology of lipid nanoparticles containing ionizable cationic lipids and siRNA. ACS Nano. 12, 4787-4795. (2018) DOI: 10.1021/acsnano.8b01516.

[10] M. Hammel, Y. Fan, A. Sarode, A.-E. Byrnes, N. Zang, P. Kou, K. Nagapudi, D. Leung, C.-C. Hoogenraad, T. Chen, C.-W. Yen, G.-L. Hura. Correlating the structure and gene silencing activity of oligonucleotide-loaded lipid nanoparticles using small-angle X-ray scattering. ACS Nano.17, 11454-11465. (2023) DOI: 10.1021/acsnano.3c01186.

[11] Z. Xu, J.-M. Seddon, P.-A. Beales, M. Rappolt, A.-I.-I. Tyler. Tyler Breaking isolation to form new networks: pH-triggered changes in connectivity inside lipid nanoparticles J Am Chem Soc. 143, pp. 16556-16565. (2021) DOI: 10.1021/jacs.1c06244.

[12] L. Uebbing, A. Ziller, C. Siewert, M.-A. Schroer, C.-E. Blanchet, D.-I. Svergun, S. Ramishetti, D. Peer, U. Sahin, H. Haas, P. Langguth. Investigation of pH-responsiveness inside lipid nanoparticles for parenteral mRNA application using small-angle X-ray scattering. Langmuir. 36, 13331-13341. (2020) DOI: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.0c02446.

[13] M. Yanez Arteta, Kjellman, T. Bartesaghi, S. Wallin, S. Wu, X. Kvist. A.-J. Dabkowska, A. Székely, N. Radulescu, A. Bergenholtz, L. Lindfors. Successful reprogramming of cellular protein production through mRNA delivered by functionalized lipid nanoparticles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115, E3351–E3360. (2018) DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1720542115.