What is SAXS?

Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS) is one of the most widely used techniques for exploring the nanometer to mesoscale structure of materials. By analyzing how X-rays are scattered at very small angles, SAXS reveals the size, shape, internal structure, and interactions of nanostructures that ultimately control material performance.

Unlike microscopy, SAXS provides statistically robust data across entire ensembles of particles in their native state, in solution, in powders, in thin films, or in bulk solids. This combination of versatility and precision makes SAXS a key method for nanoscale characterization in not only fundamental research but also industrial R&D, production, and quality control.

SAXS is widely used across disciplines:

- Soft matter such as polymers, block copolymers, surfactants, micelles, colloids, gels, and liquid crystals.

- Biological systems including proteins in solution, nucleic acids, protein–DNA/RNA complexes, viruses, virus-like particles, antibodies, and other biopharmaceuticals.

- Nanomaterials such as nanoparticles (including anisotropic particles such as rods or platelets), porous solids (e.g. silica, zeolites, MOFs), nanoclays, layered materials, and nanocomposites.

The length scales accessible extend from ~1 nm to several hundred nanometers, and with Ultra-SAXS (USAXS) even into the micron range. This continuous coverage makes SAXS uniquely suited to study hierarchical materials that span multiple structural levels.

Beyond static measurements, SAXS can be performed under controlled environments, varying temperature, humidity, stress or pressure, enabling you to monitor structural dynamics in situ and operando and to connect nanoscale organization with functional behavior.

How does SAXS work?

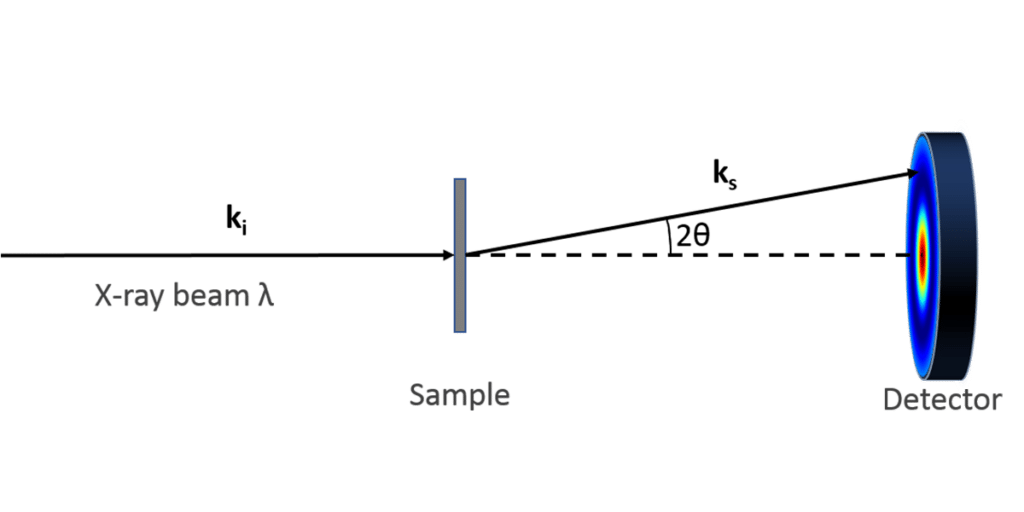

In a SAXS experiment, a highly collimated beam of monochromatic X-rays is transmitted through a thin sample, typically about 1 mm thick. Variations in electron density within the material cause the X-rays to scatter at very small angles, usually less than 5°, away from the direct beam. A two-dimensional area detector placed downstream records the scattered intensity over the full azimuthal range.

The scattering is conventionally described by the angle 2θ and the associated scattering vector

\(q = \frac{4\pi}{\lambda} \sin(\theta)\)where λ is the X-ray wavelength (commonly 0.154 nm for a Cu Kα laboratory source). The characteristic length scale being probed is given by D = 2π/q:

Small q → large structures (hundreds of nanometers to microns using USAXS).

Large q → fine features (a few nanometers).

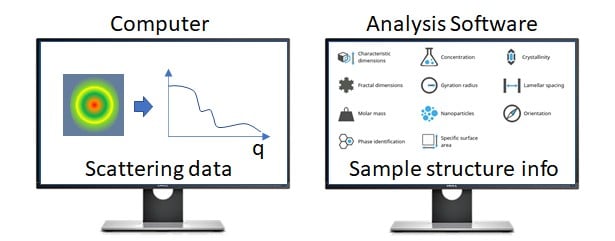

The resulting scattering curve, I(q), is like a fingerprint of the nanostructure. Sharp peaks in the scattering curve indicate well-defined periodicities, such as lamellar spacings in polymers or pore–pore distances in mesoporous materials. Broader features reflect particle form factors and size distributions, allowing identification of spheres, rods, lamellae, vesicles, or bicontinuous phases. In more complex systems, SAXS also captures interparticle correlations and hierarchical organization across multiple length scales.

To move from scattering patterns to real structures, SAXS relies on modeling the underlying electron density variations in the sample. By fitting these models to the data, SAXS provides you with quantitative descriptions of nanoscale morphology that can be directly related to material properties.

What information does SAXS provide?

A single SAXS curve can provide you with a wide range of quantitative information about structure and organization at the nanoscale. The technique captures not only the size of particles, but also their shape, internal order, and interactions, making it uniquely powerful for both materials science and biology.

Particle size and distribution

SAXS determines quantitative size distributions from ~1 nm to hundreds of nanometers, and with USAXS even into the micron range. It is routinely used to measure particle sizes and their polydispersity with high accuracy, from nanoparticles and colloids to proteins and micelles.

Shape and morphology

From spheres to rods, lamellae, vesicles, or bicontinuous structures, SAXS distinguishes between different morphologies and quantifies parameters such as aspect ratio.

Internal nanostructures and periodicities

Sharp peaks in SAXS patterns reveal ordered domains such as lamellar phase dimensions in polymers and surfactants or pore–pore distances in mesoporous materials.

Interparticle interactions and assemblies

SAXS reveals how proteins oligomerize, how colloids aggregate or repel, and how surfactants self-assemble into micelles and bilayers.

Hierarchical structures

SAXS covers a continuous length scale from nanometers to microns, making it suited for hierarchical materials that combine multiple levels of organization.

Dynamic processes

Under in situ or operando conditions, SAXS can track structural dynamics such as phase transitions, crystallization, or structural evolution under stress, temperature, or flow.

Structural biology

SAXS has long been used to study proteins, nucleic acids, viruses, and their complexes directly in solution. It provides overall shape information and, through comparison with models, can probe protein flexibility, oligomerization, and stability.

Advantages of SAXS

SAXS offers a combination of strengths that make it one of the most valuable techniques for nanoscale characterization. It is not only versatile in terms of sample types but also uniquely reliable in the quality of information it provides.

Minimal sample preparation

Measurements require no staining, drying, or freezing, preserving samples as close as possible to their natural state.

Native conditions

Study proteins in buffer, polymers in melt, nanoparticles in suspension, or materials under relevant environments.

Non-destructive

Samples remain intact and can be used for complementary analyses afterward.

Broad applicability

SAXS works across liquids, powders, thin films, and bulk solids, offering flexibility unmatched by most other techniques.

Statistical robustness

Results average over millions of particles, providing reliable, representative information rather than data from isolated regions.

Laboratory accessibility

With laboratory instruments approaching synchrotron-level performance in many applications, you gain access to high-end nanoscale analysis without relying exclusively on large facilities.

SAXS vs other techniques

Every characterization technique has its own window onto the nanoscale. By understanding the strengths of SAXS alongside other methods, you can decide which combination will reveal the most about your sample.

SAXS × TEM

Transmission Electron Microscopy excels at imaging individual particles at high resolution, while SAXS captures ensemble-averaged structural parameters across millions of particles in their native environment. One gives you detail at the local level, the other robust statistics over the whole population.

SAXS × DLS

Dynamic Light Scattering provides quick estimates of hydrodynamic size in dilute solutions but is sensitive to assumptions about shape and polydispersity. SAXS delivers highly accurate, model-independent size distributions and structural detail beyond simple diameters. Used together, they disentangle particle size, shape, and aggregation state.

SAXS × DSC

Differential Scanning Calorimetry identifies thermal events such as melting or glass transitions, while SAXS reveals the nanoscale rearrangements that cause them. Together, they link bulk thermodynamics with the underlying morphology.

SAXS × SANS

Small Angle Neutron Scattering offers unique isotopic and light-element contrast but requires large facilities. On the other hand, SAXS provides electron-density contrast with laboratory accessibility. The two probe the same length scales but from different perspectives, enriching the structural information available.

What is WAXS?

Wide-Angle X-ray Scattering (WAXS) probes shorter length scales than SAXS, reaching the regime of interatomic distances and crystalline order. At higher scattering angles (typically 5–60° or more), the technique becomes sensitive to lattice spacings on the order of Ångströms to a few nanometers.

WAXS is closely related to powder X-ray diffraction (XRD), since both detect the Bragg reflections that arise from regularly spaced atomic planes. From these reflections, one can determine unit cell parameters, crystal phases, degree of crystallinity, and preferred orientation in polycrystalline materials.

In practice, SAXS and WAXS complement each other: SAXS captures nanoscale morphology and domain organization, while WAXS provides molecular and atomic packing. Together, they establish a multiscale view essential in fields like polymers, nanocomposites, pharmaceuticals, and functional materials, where atomic arrangement and nanoscale structure together determine performance.

What is USAXS?

Ultra-Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (USAXS) extends SAXS to even lower scattering angles, pushing the accessible size range from hundreds of nanometers into the micron scale. By employing channel-cut crystal optics, USAXS can probe much larger structural features.

This makes USAXS ideal for studying:

- Hierarchical or multiphase systems where structures span from nanometers to microns.

- Porous materials with large, interconnected voids.

- Aggregates and clusters of nanoparticles or colloids.

- Polymer blends and composites with domain sizes beyond the SAXS range.

By extending SAXS into the ultra-low-q regime, USAXS opens a window onto the micron scale while maintaining seamless overlap with nanoscale measurements. Combined with SAXS and WAXS, it transforms X-ray scattering into a single experiment that can follow matter from atomic order to macroscopic texture.

What are GISAXS and GIWAXS?

Most SAXS and WAXS experiments probe the bulk of a material in transmission geometry. But when you want to study thin films, surfaces, or interfaces, Grazing-Incidence X-ray Scattering (GI techniques) becomes essential.

- GISAXS (Grazing-Incidence Small-Angle X-ray Scattering) is sensitive to nanostructures confined near the surface, typically within the top tens of nanometers. It reveals features such as surface morphology, patterning, and near-surface assemblies.

- GIWAXS (Grazing-Incidence Wide-Angle X-ray Scattering) extends this view to the atomic scale, capturing crystallinity, molecular orientation, and packing in thin films and interfacial layers.

Together, GISAXS and GIWAXS are powerful tools for fields like:

- Semiconductors and organic electronics — to probe molecular orientation and packing in active layers.Nanostructured coatings and catalysts — to study surface morphology, porosity, and ordering.

- Polymer thin films and block copolymers — to map domain orientation and long-range ordering.

By combining transmission geometries (SAXS/WAXS/USAXS) with grazing-incidence approaches (GISAXS/GIWAXS), you can connect bulk structure with surface architecture in one experimental framework, an integrated perspective that is critical for materials where interfacial properties govern performance.